I speak with a lot of technical and non-technical people in our ModernAgile community.

As you are likely aware, one of the goals of agile methods was to bring business and development people together.

Sadly, when it comes to topics like refactoring and code cruft (often mistakenly referred to as “technical debt”) we find a point of contention and conflict.

The development staff wants to stop and fix/reform the code base, but the management rightly sees that doing so will mean no new features will be shipped for some time. It’s an interruption, and the return on investment is uncertain. Will we really have lower defects and faster development later if we do this?

What is to be done?

In hopes of healing the divide, I’ve tried to explain cruft in a metaphor. What you do with your understanding is up to you, but I’ve added some notes at the bottom of the post, and I welcome your questions.

The Dreadful User Interface

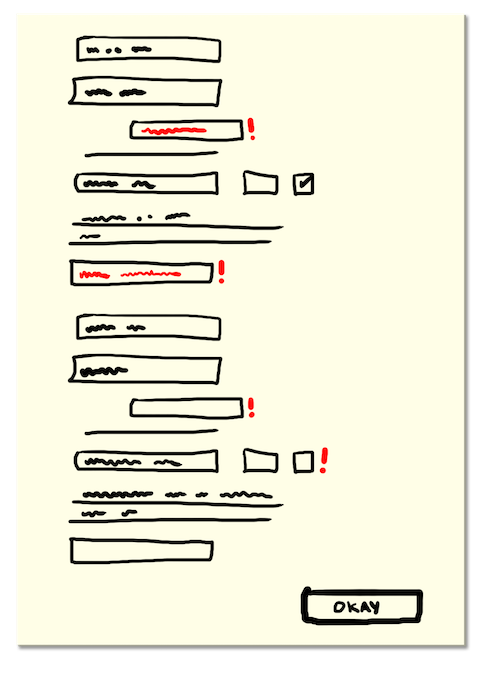

You have a program you have to use every day. It has 48 fields on one screen, and an “okay” button at the bottom.

What happens when you press okay depends on which fields you fill in.

If you fill in fields 1–4, 12, 32, and 48 (you may have to scroll a bit) then it will create a new account, but don’t touch fields other than those or it will attempt to either update or delete the account listed in field 32.

If you want to add a feature to the account, don’t even touch field 3 or it will fail outright without an error message.

Enter fields 1, and 5–8 if you want to transfer ownership of the account. Don’t touch any of the other fields or it may transfer to a random account.

So always fill in exactly the right fields, exactly the right way, and then click “OK.”

If you are really careful it will work.

If you make a mistake it may fail.

You use this system all day every day. When it fails, it will quietly do nothing, or quietly do the wrong thing. It will look like it worked until you see the damage that was done and you have to undo it.

You spend a lot of time repairing the damage, up to 80% of your total working time1.

Now, you CAN do your job using this software. It’s hard to bring new people up to speed and they are always making mistakes with it, but a skillful and careful operator can use it successfully most of the time.

Now here is the fun part:

The vendor constantly adds new fields to the form. Each field may impact any number of workflows - so that if you touch field 3 you must NOT touch new field 49, or if you fill in 49 you MUST NOT leave field 32 blank.

This messy user interface is what crufty code is like on the inside.

- It’s “thorny” – you have to be extremely careful2

- You can’t tell if your changes are safe

- Errors aren’t obvious

- There is no safety against missteps

- It takes new devs months to get on board

- A lot of time is wasted fixing errors

- Changes frequently have surprising effects

Does this sound familiar?

“Don’t fix the technical debt, just add features” sounds practical on the surface, but it leaves this constant hazard and the struggle to manage it in place. Not only does the problem remain, but it also gets worse with time.

What of the people begging permission to fix their ongoing problems? We may ignore them and/or label them as whiners. “Those people are always complaining,” folks will say, “so it clearly doesn’t mean anything.”

Maybe if they’re always complaining about the code quality it’s because it’s really that bad and getting worse? What if those people are right?

How Do Developers Remediate Cruft?

Take the above example, and imagine that we fix it. Instead of putting all the fields on one screen and inferring the user’s intention from the fields that were filled in, we create specific dialogs for each user action, and only include the fields that they may safely use to perform that function.

Maybe we’ll end up with a dozen smaller UI screens, each with a handful of data fields on it. The top-level screen/menu could have selections like “create an account,” “renew a subscription,” and “change payment information.”

To “transfer assets” we only have to deal with the one flow and its data in a single dialog. We won’t accidentally trip any of the other flows or misinterpret the user’s intentions.

Since each dialogue only does one thing, it’s easy to add validation and error reporting.

The new system is simpler because it is divided into meaningful modules. This helps new people use it correctly on their first try.

It doesn’t do anything new, but those things that it did before are much easier to do without making errors. The experience of using the form is transformed.

This is rather like the way that developers work on the internals of the application.

In software development, creating a more useful structure without changing functionality is called “refactoring.”

Whereas in the dreadful ui example we break a screen of fields into separate dialogs, in code we break up piles of variables (data) and functions (behavior) into more meaningful and focused units.

This way it is easier to find and modify code, with far fewer potential side effects like errors or data corruption.

This code is broken into modules, libraries, classes, or sometimes rearchitected into separate services or microservices (all technical ways to not have everything all thrown together in a jumble).

Avoiding accidental breakage is crucial as the application grows larger and more complicated. We should not leave the code wide open to accidental misuse.

It’s hard for users and managers to see this refactoring because it is changing only the developers’ interface to the code, but the effects of refactoring should show up as a trailing indicator: is it easier, safer, faster now?

And there is the truth that the teams have been trying to communicate all along:

We refactor to make it easier, faster, and safer to continue adding functionality.

What if we do all this work and it’s not easier? Well, then we have refactored it the wrong way (which we could also do with the messy form UI we described above) and they may have to make more adjustments.

Refactoring is a skill and skills take time to develop. We may need some help learning to do it safely and well.

There is a caveat here: Sometimes people claim to be refactoring, but they’re really just rewriting code or making a bunch of changes without tests; you can tell because the programs don’t work for hours, days, or even weeks. If you see “refactoring” happening without tests or commits, get some training for your team.

What Strategies Can We Use?

Do you want to have a better developer experience, resulting in good work done well, sooner, and more frequently? Great!

There are a few strategies employed to good effect here:

- Don’t let it get bad. Minutes of refactoring every hour can keep a code base clean. You don’t want your code base to become so miserable that you need days of refactoring all at once. If you’re starting fresh, always refactor as part of your normal TDD cycle. It’s free, it’s fast, and you avoid having to choose between the following strategies.

- Continuous remedial refactoring involves adding tests and refactoring code as you go into a crufty codebase to add features. This isn’t easy, because the first one into some messy area may have a lot of cleanup work to do. Allow extra time for each task. Consider having programmers work in groups when they first enter a crufty section of source code (if not always). The idea here is to only refactor the code that impedes them, not all the code that exists.

- You can set aside a weekly budget for bigger refactorings outside of normal feature work — on the order of a day a week. Again, working in groups is recommended (3-7 people is reasonable).

- Kill the project. Drop the product, take down the production instances, disband the team. You can eliminate the whole code base this way and repurpose the people to do something more valuable. This isn’t an option if the codebase is your primary stream of revenue, but may work for peripheral apps.

- You can try to switch companies before it gets too bad (“run away!”), so it’s someone else’s problem. When you get to the new job, try to take strategy #1, above. This sounds tongue-in-cheek but we have observed this strategy in the wild and include it for completeness.

- You can hire a company to come in and reform your code base. There are refactoring-as-a-service companies. This will cause some disruption as the refactored code will be unfamiliar to the staff programmers, but it should be more maintainable eventually so it may be a net positive.

- You can schedule a rewrite. This is the least successful of all the strategies on this list, but it has sometimes worked out. I’m not sure of the success rate, but I think it’s less than 50% because even a rewrite requires that we stop loading the “old version” with new features long enough to get the new version up to parity.

Note that items 4-7 can leave the team’s habits unchanged, leading to a recurrence of the problem.

The first few strategies (1-3) can be combined. You may refactor on-the-fly, slow down to tidy up, and have a weekly session for big whole-team refactorings. Any combination is helpful.

If your teams are going to be refactoring, ensure that your developers are trained in the art and discipline of refactoring, because even highly experienced developers may lack the skills of successful refactoring.